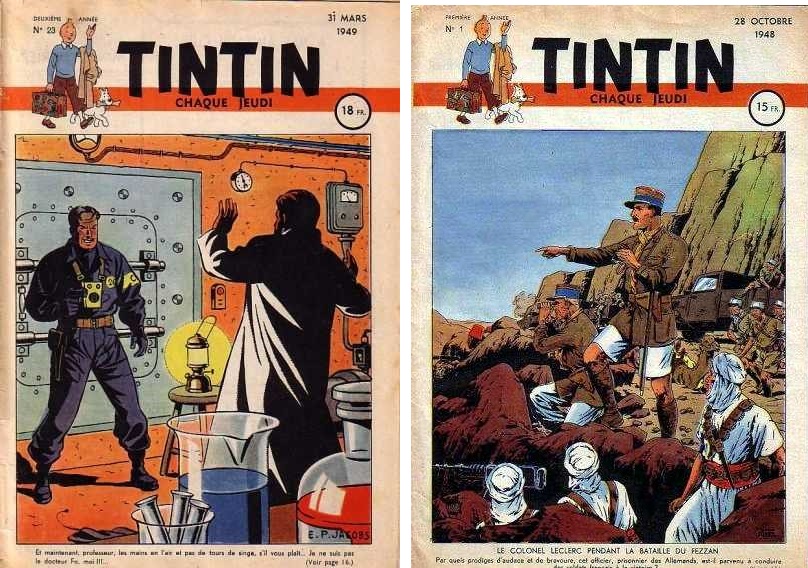

Le Journal Tintin (founded in 1946 in Brussels)

Le Journal Tintin was a family-friendly weekly: “Le journal des jeunes de 7 à 77 ans.” Many stories fell into the adventure genre.

Hergé (portrait: https://www.lambiek.net/artists/h/herge.htm) brought the drawing technique called “ligne claire” to a level of command that earned him the status of a pioneer. His style and technique were soon adopted by Edgar P. Jacobs, the author of Blake & Mortimer (above, on the right).

The high readability of Hergé’s drawings was coupled with a sophisticated use of layout, which is essential to suggest movement. Hergé drew inspiration from cinema, but while a film decomposes movement displaying every part, comic artists have to choose a few snapshots, carefully selected so that the reader’s imagination can fill the gaps between pictures.

Le Journal Spirou (founded in 1938 in Charleroi)

Its artists developed a modern style based on caricature (large heads and big noses). It featured rounder speech balloons instead of rectangles and favoured short, informal exchanges over long speeches.

Some famous names: André Franquin (Les Aventures de Spirou et Fantasio), Peyo (Les Schtroumpfs), Morris (Lucky Luke), Jean Roba (Boule & Bill). With its sparing use of text, this type of comic explored the resources of graphic design at various levels.

As you can see here, Spirou artists developed a wider diversity of onomatopoeias (the volume depends on the size and thickness of the letters) and multiplied graphic codes (straight or spiral lines, stars, drops, puffs of dust, symbols suggesting swearing) in order to suggest emotions and tones of voice. The images suggest a wealth of sounds. Poses and facial expressions are exaggerated, bodies are distorted by moves and impacts.

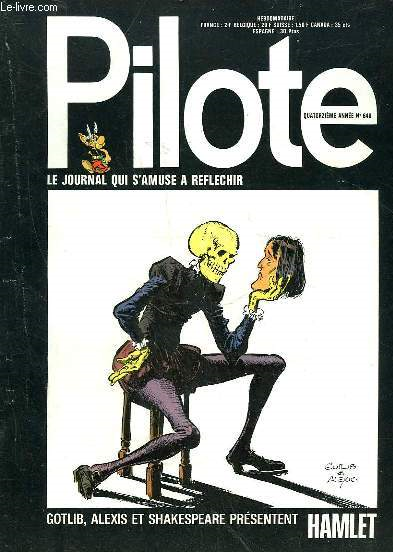

Pilote (founded in 1959)

This French weekly was originally a magazine for teenagers, but it was increasingly dominated by BDs for adults. Many future famous artists contributed to it: Jean-Michel Charlier, Marcel Gotlib, Alexis, Fred, Claire Bretécher, Moebius, Jean-Claude Mézières, Hugo Pratt, among others.

Two of Pilote’s founders, Goscinny and Uderzo, created Astérix le Gaulois. The stories were popular among a very large audience as children would enjoy the stories and Obélix’s fights with the Romans while adults would appreciate private jokes (caricatures of celebrities, anachronisms based on a combination of Ancient time references with daily-life realities typical of 1970s France, names based on puns). For that matter, Astérix provides a fascinating insight into French culture, but it represents a challenge for translators, the gags often resting upon cultural specificities which do not necessarily have their counterpart in other countries and languages.

Goscinny liked to play with cultural misunderstandings. When different languages are signaled by font effects, the joke is easy to transpose into another language. (See cases no. 2 and 4: http://goscinny.free.fr/Traduction.htm and http://www.asterix.com/the-collection/translations/)

Yet, translating Astérix in Brittany in English turned out to be much more difficult.

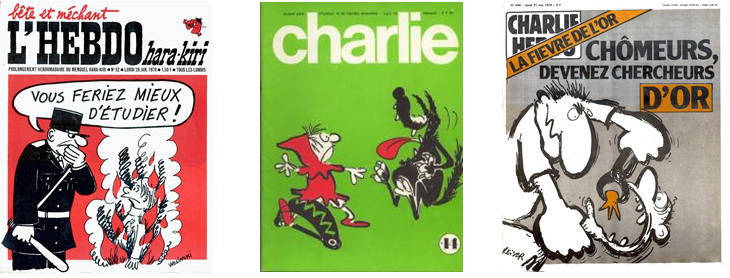

Alternative, satirical BDs (1960-70s)

The spirit following the student revolt and the strikes of May 1968 in France entailed a trend of anti-establishment protests in every field. Several BD artists felt the urge to expose hypocrisy, social problems, colonialism, racism, misogyny, police control, and many other political issues. The 1970s witnessed the rise of many alternative magazines for adults; they were provocative, subversive, and representative of the counter-culture (Charlie mensuel, Fluide glacial, Hara-Kiri, L’Echo des savanes, Bodoï, Charlie Hebdo). Satirists opted for dirtier, rougher drawings aiming at expressing the violence of their anti-establishment revolt, and resorting largely to dark humour.

Important names are Reiser, Cabu, Wolinski, Bretécher, Vuillemin.

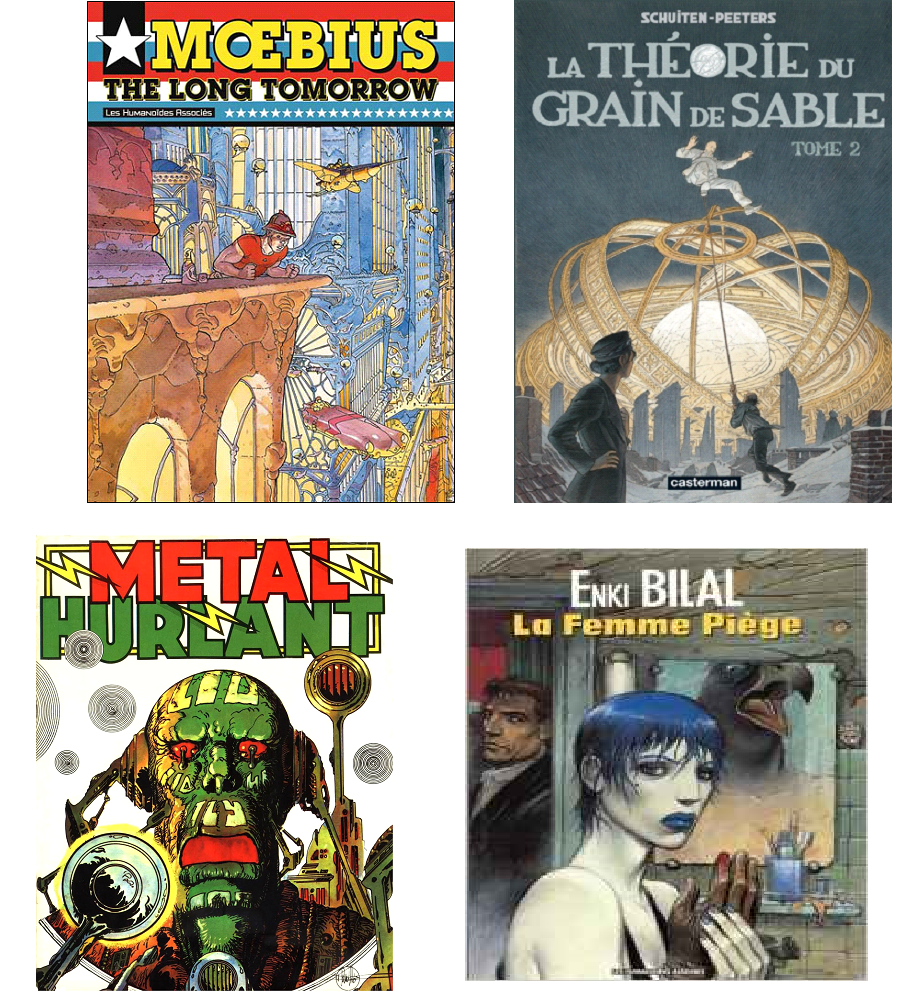

The Great Illustrators (1980s)

The early 1980s saw printing firms changing their publication policy in favour of multi-episode series aimed at being primarily sold as albums. Contrary to past magazines which published full series, the periodical (A suivre...) (to be continued) displayed a few pages in order to tempt readers into buying beautiful, luxurious hard-covers. Serials imposed generally the purchase of a dozen or more volumes in order to read the full story. The format offered illustrators the opportunity to enrich BDs with lavish, sumptuous artwork like Moebius, François Schuiten, Philippe Druillet, Enki Bilal.

For various effects, others used the technique of “couleur directe”, which means that colours are not added to a preexisting black and white inked drawing. In fact, each frame is composed like a small painting. See for example Vink (Le Moine fou)or Alex Barbier.

The “auteur” comic books (1980-90s)

Some artists brought BD to the level of the finest literature. Dealing with history with such precision and playing on classic literary references, they created very personal universes and contributed to legitimizing BD as a ‛serious’ form of artistic expression.

Hugo Pratt’s series Corto Maltese created an attractive character in a combination of exoticism, adventure, and romanticism. Travelling through all continents, Corto is involved, against his will, in many of the major historical events of the early 20th Century, sometimes meeting famous historical figures.

Jacques Tardi composed a number of albums on WWIand WWII. He also devoted a series to the dramatic events of the “Commune de Paris” in 1870 (one of the last workers revolutions). Finally, he created dark thrillers with the adventures of Adèle Blanc-Sec and Nestor Burma.

In addition to their talents as scenarists, Pratt and Tardi’s beautifully crafted illustrations inspired other Franco-Belgian BD artists who started using black and white aesthetics.

The French graphic novel

Apart from the aforementioned artists, from the 1980s onward, mainstream publishers have been churning out long series of uneven quality. Nevertheless, sales kept going up. Collections devoted to specific genres (thriller, sci-fi, crime, historical, etc.) welcome script-writers able to produce multi-episode sagas increasingly influenced by Hollywood action movies and heroic fantasy.

A new generation of artists felt constrained by such boundaries. Inspired by American underground graphic novels, they gave up the large format for smaller ones, and created soft-cover stories. Either they transgressed existing genres through parody or they heralded new genres.

Often interested in children book aesthetics, they develop adult stories with an unusual kind of humour based on the discrepancy between naïvety and sarcastic dialogues.

Definitely recognized as a serious means of expression, graphic novels have also promoted biographies, diaries, historical testimonies and travel reports. These artists are less interested in displaying visual dexterity than in seeking for novel ways of exploring more complex topics and psychological experiences.

Some important names: David B., Marjane Satrapi, Emmanuel Guibert, Lewis Trondheim, Joann Sfar, Clément Oubrerie.